Fishing out the gene pool

Practical Action

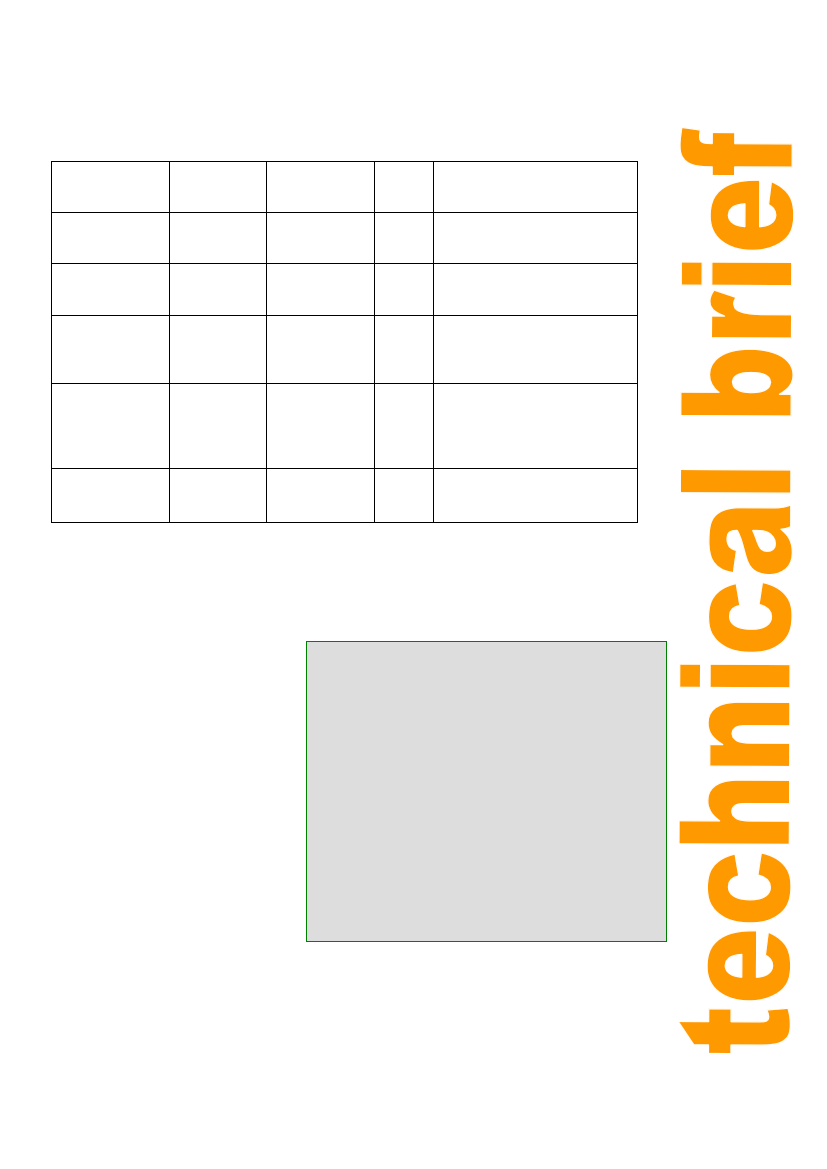

Table 1. Kerala marine fish landings 1970-90 (All figures in '000 tonnes)

Until 1970, fish catches in the artisanal sector had been steadily increasing; 90-100 per cent of

production came from non-motorized traditional craft It is also important to note that over the 1960s as

much as 70 per cent of the prawn catch came from fishermen using these craft and traditional gears.

Year

Traditional Mechanised

Total Remarks

sector

sector landing

Landings

1970

1971

340 53

390 47

393

445

Both sectors largely complementary,

adding to total production.

1972

257 39

296

1973

1974

355 94

320 101

449

421

Competition for product starts between

both sectors but total landings peak

1975

241 180

421

1976

1977

1978

1980

272 59

238 107

256 118

144 135

331

345

374

279

Overall production declines drastically.

Intensifying competition for resources

by the mechanized sector at the cost

of the traditional sector.

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

201 73

240 85

287 98

263 130

197 129

274

325

385

393

326

Outboard motors taken up rapidly,

boosting the artisanal share,

Increasingly, catches from the

motorized ring seines dominate the

artisanal catch.

1986

1987

1990

252 131

152 151

250 150

383

303

400a

By the end of the decade catches

approach pre-1970 levels, but with

wide fluctuations. Non-motorized

fishing almost entirely displaced.

Modem development strategies for fisheries have generally been based on industrial

processes, where production is not seen to be limited by resource constraints, and where

short-term economic gain and super-efficient hunting technology rule. The capacity of fish

stocks to replenish themselves is limited; however, and the optimistic economic projections

that have justified the huge investment in industrial fishing technology worldwide have not

taken these resource constraints into consideration.

Overfishing problems generally arise

when interests from outside the

fishing communities invest in new

technology: commercial interests that

are either not aware of traditional

taboos and community controls -or not

bound by them. In Europe thousands

of small-scale fishermen were

displaced by the introduction of

trawling and steam drift-netting before

the turn of the twentieth century.

Prawn Trawlers wreak havoc on reefs

The fishing communities of five coastal villages (Pallithottam,

Port Quilon, Moothakara, Vaddy and Thagassiry) next to the

town of Quilon have been particularly hit by the introduction

of pawn trawling. Situated some 10km south of what is

probably India’s largest trawler base – Neendakara – their

fishing grounds have been devastated by the uncontrolled

plundering of thousands of trawlers. Mr Andrews, a fisherman

from the village of Port Quilon (and Secretary to the local

fishworker organisation), has studied and documented the

impact of these trawlers on the fishing grounds and of the

Similarly, the introduction of trawling

fish stocks. His underwater maps show how the trawlers have

destroyed the sand bars and delicate reef structures that play

technology to Kerala in south-western such a key role in the reproductive and production cycle of

India is threatening the livelihoods of

marine life. He has listed some 150 once-common species

hundreds of thousands of artisanal

fishworkers who depend upon inshore

fishing. Investment in prawn-trawlers

was actively supported by the Kerala

(including some 135 fin fish species) that have been severely

depleted by the uncontrolled trawl fishing, to the extent that

they are no longer caught in the area by the artisanal

fishermen.

Government in the 1960s, and by 1970 a sizeable fleet had been built up. During the 1970s

the artisanal fish-catch fell dramatically, and by 1980 their share was 45 per cent of the

1970 level (see Table 1). The desperate response of many small-scale fishworkers was to

react with violence and to invest in more intensive fishing technology to compete with the

trawlers.

3